Sheldon Group

We study a broad range of topics relating to evolutionary biology, ecology and behavioural ecology. Our current research centres on four main areas:

1. The Ecology of Spring Timing

Tits produce large broods of young compared to most bird species. They are able to do this because they utilise the superabundance of caterpillars that hatch in deciduous woodlands every spring. However, this caterpillar peak is short-lived - caterpillars hatch out when the leaves of trees, such as oaks, begin to unfurl, but can only feed on young leaves, meaning they will only be available to the birds for a couple of weeks. When birds should start laying their clutch is therefore a crucial decision - if parents get it wrong, and lay too early or too late relative to the peak in caterpillar availability, they may not be able to find enough food to keep their brood alive.

Using our tit breeding records spanning the last 6 decades, we have shown that the tits are now laying about 2 weeks earlier than they did in the 1960, inline with climate change (read more here). However, our recent research has revealed that this shift in the timing in response to climate change varies considerably across the woodland with the slowest nesting sites only having advanced egg laying by 7.5 days, whilst the fastest sites advanced by 25.6 days. This variation is linked to the health of nearby oak trees - birds breeding in areas with healthy oaks have advanced their laying by 5.4 days more than those breeding in areas with unhealthy oaks (read more here).

PhenoScale: The Importance of Spatial Scale for Ecological & Evolutionary Processes

We know that climate change is driving large scale changes in the timing of seasonal events, affecting plants and animals across the globe. But how much does this matters for the survival and reproduction of these organisms, and ultimately how they will be affected by climate change? The central premise of a current UKRI-funded 5-year project awarded to Ben Sheldon is that a major reason for that lack of understanding is that we haven’t focussed enough on the right spatial scale. By combining measures of the timing of leaf-out for hundreds of thousands of trees across Wytham Woods, with data on insects and birds that rely on these trees for food, we will be able to work out how much the effects of climate change are driven by effects at small and large scales.

We fly WingtraOne GEN II drones carrying multispectral cameras (MicaSense RedEdge-P) repeatedly over Wytham Woods thoughtout spring to capture vegetation phenology at the scale of individual trees. Images are stitched to create NDVI orthomosaics for the entire woodland. Central image shows an NDVI orthomosaic for a single flight in late March 2023, before most trees had come into leaf. Right-hand image shows an individual oak crown. Image ground sampling distance was ~3 cm / pixel, flying at ~100 m agl.

2. The Role of Social Processes in Evolutionary Ecology

Another focus of our research is to better understand the causes of individual variation in social behaviour and the consequences of social structure for a range of processes, including information spread.

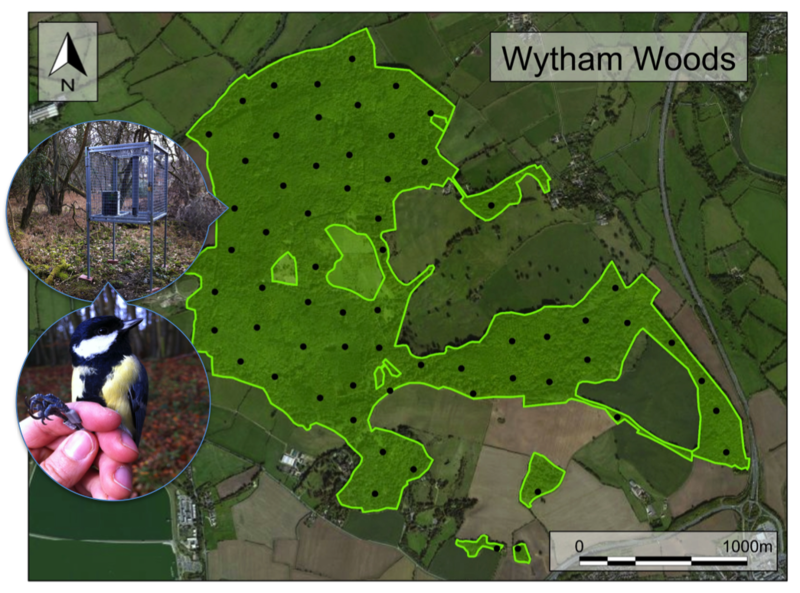

How individuals interact with one another is likely to have important consequences for their lives. Through tracking the activity and movements of thousands of individual birds in Wytham, we can monitor the social interactions within winter feeding flocks. We do this using “smart” bird feeders, which are put up in the woods and open for two days a week. Each feeder has RFID tag readers that detect every tagged bird that comes to feed. This gives a snapshot of who is feeding with whom, allowing us to test how individuals differ in their social behaviour, who they form strong social bonds with, and how the environment shapes their societies.

Measuring social behaviour: each black dot here is a bird feeder fitted with detectors that will record a bird's identity every time it lands to feed. This tell us which birds are feeding together. We open these feeders for two days a week throughout autumn and winter, allowing us to closely monitor the birds' behaviour across the seasons.

3. Quantitative & molecular genetics

For almost any characteristic of wild animals and plants that we can measure, we observe variation. Why do individuals differ from one another? One of the ways to answer this question is to use different kinds of genetic analysis to work out how much variation is due to the environment, and how much due to genetic differences between individuals. Tits have been a very suitable species to try to do this sort of work, particularly because it is easy to match together parents and their offspring by simply catching and identifying parents, and by ringing nestlings at the nest.

One of the classic approaches to this question is called quantitative genetics. This refers to an approach where it is assumed that traits are influenced by many genes that each have very small effects. By working out what proportion of genes we expect to be shared between different kinds of relative (e.g. parents and offspring share half their genes; first cousins share only one eighth of their genes) and comparing how similar their phenotypes are, we can estimate the relative importance of genetic versus other kinds (e.g. environmental) of variation. Such work has been a particular focus over the past decade or so, but one of the earliest estimates of the heritability of a trait in a wild animal population came from Wytham great tits, with Perrins & Jones study of clutch size heritability in 1974.

4. Ecology and Epidemiology of Avian Diseases

In recent years we have broadened our understanding of the tits in Wytham by considering the way that infectious diseases spread among, and affect, the different tit species. One disease that some find surprising to learn infects birds in the UK is malaria. Far from being a largely tropical disease as in humans, avian malaria can be found in birds in very many parts of the world. There are several different types of malaria parasite, but one group - Plasmodium - is quite closely related to the parasites that cause human malaria (there is no danger of humans becoming infected by bird malarias however!). Focussing particularly on blue tits, and to a lesser extent on great tits, we have explored when and where malaria infections occur and what effect they have when then do so.

A second disease that we have worked on was a novel outbreak of avian pox among birds. Infecting mostly great tits (and to a lesser extent other tit species), this infection, caused by a pox virus, was first noted in the UK in Surrey in 2006. It spread rapidly through England and reached Wytham by 2009, and by 2010 almost 10% of birds showed symptoms. Alarmed by this, we obtained an Urgency grant from NERC to study this new disease together with colleagues at the Institute of Zoology. Our studies, which were aided enormously by records from the public of birds in gardens, documented the spread of this disease as well as showing that it had serious effects for infected birds. Thankfully, the infection rate seems to have declined, at least locally, though we still find occasional records of infected birds.

If you are interested in joining our research group, please take a look at our currently available positions below.

Fellowships

Please get in touch with Prof Ben Sheldon (ben.sheldon@biology.ox.ac.uk) if you are considering applying for a fellowship to join the group.

DPhil studentships

Available funded positions will be advertised below, but we are always happy to hear from prospective students.

Academics in the group who can supervise:

Prof Ben Sheldon (ben.sheldon@biology.ox.ac.uk)

Dr Ella Cole (eleanor.cole@biology.ox.ac.uk)

Fieldwork assistant positions

We frequently advertise fieldwork assistant positions during spring each year to help with collection of bird breeding data for the long-term monitoring of tits, as well as phenological data for the PhenoScale project at Wytham Woods.

Currently available opportunities

About the Wytham Tit Study

Features in nature documentaries

https://www.youtube.com/embed/gmUmSK9RxjU?si=fslOHAGQDtFPcSV-

BBC Springwatch featured some of our research exploring the importance of spring timing for tits

Our research on incubation behaviour featured on ‘Attenborough’s Wonder of Eggs’

Sir David Attenborough visits Wytham and talks about the importance of spring timing

Field diaries

https://www.youtube.com/embed/C-rmBE41nSs?si=BOR2DuUIWYgVcmWj

Wytham Woods: A Season in 3 Boxes

Life in the Field(work)

Meet your bird neighbours

About our research

https://www.youtube.com/embed/XYr5P3bk2ek?si=cnDBUzUA0spJplLn

Science Of The Times podcast: Not all birds are the same

Life-history trade-offs and the role of feather quality

Social networks and culture in birds